By Sonia Taitz

“It’s the most delicate thing in the world, to do what I did,” says Joseph Papp, producer of the New York Shakespeare Festival. What Mr. Papp did was temporarily close down Harry Kondoleon’s newest play, “Zero Positive,” after a week of previews, 11 days before its scheduled opening night. Within two days, both the leading actor and the director had been replaced.

Remarkably, the show, a comic exploration of mortality, is scheduled to open this Thursday at the Public Theater/LuEasther Hall, a mere two weeks behind its original schedule. More remarkably, the transition, apparently, was fairly amicable.

“It isn’t always,” said the producer. “Harry thought that Reed Birney, though a wonderful, naturalistic actor, was miscast.

“There’s a unique style to this playwright’s work,” Mr. Papp said. “A snap to it, a verbal brilliance, that was getting lost. It isn’t a lyrical play. Still, I might have given it more time.” So would the play’s director, Mark Linn-Baker (perhaps best known as a star of “Perfect Strangers,” the television comedy). “Mark was getting depressed, overwhelmed, at even considering the notion of replacing an actor,” said Mr. Papp. “That’s because he’s an actor fundamentally; he identified. So I explained to Harry that if we let Reed go, we might lose Mark as well.”

Mr. Kondoleon saw the issue less ambiguously: “We made an error. I felt we had to correct it. There was a consensus to wait a little longer. My answer was ‘N-O.’” Eventually (“Harry doesn’t stop complaining, but I’m glad he insisted,” says Mr. Papp), the producer stood in front of one preview audience and asked them what they thought. Based on their mixed comments, he decided to temporarily close the show.

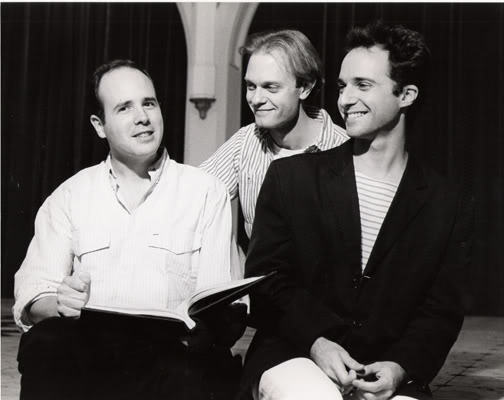

Replacing Mr. Birney (who declined to comment on his dismissal) is David Pierce, who played Laertes in the Shakespeare Festival’s last production of “Hamlet,” and Yasha in Peter Brook’s recent staging of “The Cherry Orchard” at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Mr. Pierce (below, center) will portray Himmer, a young man whose discovery that he has tested positive for the AIDS virus – but not the disease – catalyzes the action of “Zero Positive.” “At first I felt a little guilty,” the actor said. “But there is so much to do – this is such hard material – that I can’t tell you how it feels anymore. I will say this: When Mr. Papp called and said, “’I bet you’re surprised to hear from me,’ I definitely was.”

For the new director, Kenneth Elliott (above, left, with Mr. Pierce and Mr. Kondoleon), “Zero Positive” will be one of three plays running simultaneously in New York; the other two are “Vampire Lesbians of Sodom” and “Psycho Beach Party.” “I never saw the shows before,” said Mr. Elliott, with a trace of apprehension. “But my approach, I think, is a little different. I kind of feel that it needs to be more energetic, with an upbeat, comic attitude. That’s what I find in the text.” Mr. Linn-Baker, now making a film in Munich, was unavailable for comment.

“This whole thing was difficult,” said Mr. Papp. “I worried about the people involved in the show. You don’t hurt actors and directors. They depend on their egos to stay alive. Reed said, ‘Well, that’s show business.’” He was very courageous. I said, ‘No, that isn’t show business.’ I think I felt lousier than he did.”

Mr. Kondoleon said simply, “I’m not bloody-happy. I’ve never done this before. But playwrights have a lot of rights, you know. I exercised them.”

The playwright’s given name may yield a clue to his tenacious, perfectionist talent. “In Greek, Harry means ‘carrier of joy,’” he said. “But in English it means ‘to bother, to annoy.’” For the son of a Greek-American accountant father called Sophocles and a mother named Athena, this paradox is neither especially troubling nor new. Since graduating from Yale Drama School seven years ago, Mr. Kondoleon, 33, has been delivering his oddly hilarious plays to a public both bothered and joyful.

The effect is intentional. “I’m not considered a ‘realistic’ playwright. But I think I’m more realistic,” said Mr. Kondoleon. “As opposed to harping on the same one problem, very slowly, with a so-called verisimilitude, I just think, ‘Oh, how boring.’ Moment to moment we transform how we feel, like quicksilver. Because of the media, one is capable of leaping from hair conditioner to news clips of the latest disaster. In fact, unfortunately, we do it too well.”

In “Zero Positive,” the “latest disaster” is not just AIDS, said Mr. Kondoleon, but more globally, “the mood of communal fear and grief that the epidemic has created.” As handled by the playwright, however, the grim premise forecloses no notions, comedy included.

“All my plays, I think, are basically funny even when they’re sad or tragic,” said the playwright, whose works, which have played at a variety of theaters, include “Anteroom,” “Christmas on Mars,” “The Vampires,” “The Fairy Garden,” and “Slacks and Tops.” “This play is about the various aspects of grief, including humor, in the face of mortality,” he concluded, with a voice that is simultaneously antic and refined.

“I think people deal with gray situations which involve a lot of pain with laughter,” he said. “I’m often shocked by how people act at funerals. They can be like surprise parties. Still, to laugh in the face of that which we can’t control is an aspect of human nature.”

“Zero Positive” begins just after the funeral of Lolly, who is never seen, but whose death sets the stage for the action. Her former husband, Jacob Blank, shaken by the loss of the woman he loved but couldn’t live with, has gone senile and intermittently mute. He plays, somewhat irritably, with an elaborate “whistling” train set. The dead woman’s son, Himmer, entertains his two close friends, Prentice and Samantha, with salad, tea, and chitchat.

During an afternoon of gossip, appalled sadness and bursts of uncontrollable giggles, Samantha tells Himmer that both she and he have tested “seropositive,” indicating that they have the AIDS virus. (The word AIDS is not mentioned here or elsewhere.) The set darkens, and Mr. Blank’s trains circle quietly around their miniature, illuminated world.

“At times,” said Mr. Kondoleon, “I go overboard in terms of the audience wondering, ‘Is this supposed to be taken seriously? Is this broad farce?’ but I like the slippery rock under your feet; it keeps you awake and alive.” The subject of theatrical delight is never far from this writer’s mind.

“I have often sat down and thought, ‘What really is fun to look at in the theater?’ In ‘Slacks and Tops,’ I thought, ‘These people are obsessed with going to Africa. What would really be extraordinary is if green, growing jungle plants burst in right through the windows.’ In ‘The Fairy Garden,’ I thought, ‘People like to hear songs sung.’ So I had the fairy sing a song. And I thought, ‘People like to see people take their clothes off. So I had someone” – a male stripper known as the Mechanic – “take their clothes off.”

In Mr. Kondoleon’s latest play, perhaps not surprisingly, there is both song and stripping. There is also a play within a play, which, he said, is “something I’ve always been attracted to. In ‘The vampires,’ I had my characters all in a fever about putting on a play which you never see. I like that theatrical metaphor. It evokes almost a childlike quality of enjoying a play that theater retains over other arts, that quality of evoking childhood wonder.”

The play within “zero Positive” is called “The Ruins of Athens,” written by Lolly when she was 19, and discovered after her funeral. The last scene of “Zero Positive” is the staging of this “costume play.”

While Mr. Kondoleon’s influences are eclectic (“I like Beckett – and Ibsen”), the classic stage provides one sturdy prototype. In “Christmas on Mars,” as in the final “Ruins of Athens” scene of “Zero Positive,” the stage is almost bare. “It’s like original Greek comedy or tragedy,” the playwright said. “You don’t have actors slouching on couches; you don’t have chairs and kitchens and things. What you have is actors in a space, conjuring the world they’re supposed to be in through language.”

In both plays the empty set is logically explained. (“Christmas” takes place in a new Upper West Side apartment, scouted by an expectant couple; “Ruins” in a hospital solarium.) “I force a non-naturalistic image, that of the Greek discourse, into a naturalistic context,” said the writer, “and in a weird way, the audience really understands that.” Often, too, his characters are robed in nightgowns or dressing gowns or hospital gowns – “They look like robes and togas to me.”

Another influence is Balinese theater, which Mr. Kondoleon studied first-hand on a grant when he was 22. In Bali, he observed puppet shows, masked dances and trance theater. “Art there is ritual. Theater is religion. They are really trying to entertain the gods,” said the playwright, whose aquiline features caused him, for 10 months, to be stared at and “patted and stroked” by the curious Balinese.

“I did believe in the ceremonies, actually,” he said. “There were little girls thought to be straight from heaven, tutored by the angels. Totally untrained, they would enter trances on the shoulders of men, dancing in total syncopation. Even if you were the biggest Doubting Thomas around, you’d wonder, ‘How could they dance like that, with their eyes shut?’”

Dances and trances are employed in “Zero Positive.” And Mr. Kondoleon’s “The Poets’ Corner” – which opens later this month at the East Village’s Theater for the New City and is based on the feud between Sylvia Plath and her husband, Ted Hughes – begins with a sadly funny puppet show in which both characters bicker tirelessly from beyond the grave.

Blood feuds and sexual pairings in the modern Western mode have also long interested Mr. Kondoleon, who has recently completed a film script that he describes as “sort of a Hitchcock thriller, which is very much to my taste. I like that genre of the husband and wife, and one wants to kill the other, and you don’t know which is which. Or who wants to do it more.” Indeed, most of his plays are based on themes of jealousy, abandonment and betrayal. In this context, “Zero Positive” sounds a new and gentler note. “I think I’ve gotten away from a kind of mean-spiritedness, an acerbic kind of flavor.”

Mr. Papp allows that “while I always loved Harry’s verve – I mean, he’s meshuggeh, totally wild, and one of the best writers around – I felt there was something destructive about him, a sense of annihilation constantly present in his work. Here he’s generated for the first time a kind of message, a potent life mystery that comes in through your pores. He’s found a way to deal with his demons.”

Mr. Kondoleon, slightly wary of “sounding too Pollyana,” has recently come “to believe in sending out messages that are nutritious. Rather than tell you that even the Evian water has radiation in it, I’ll say, ‘Wouldn’t you like a nice cool glass of good water?’”

Good water, in this case, is friendship, which forms the cool core of “Zero Positive.” In the face of a sick world, Himmer, Prentice and Samantha forgive, and promise to “have some love for,” each other. “For me, that moment is the most moving,” said Mr. Kondoleon. “I fought the impulse to matchmake people – the way it happens in Shakespeare or Restoration drama – just because they’re in the same room.

“It’s easy to say, ‘I’m so attracted to you.’ In friendship, which you don’t often see depicted, there is a delicacy that’s very special. It’s even more valued in 1988 because everything is challenged. People don’t know what to make of marriages that don’t last – and lovers dropping dead around them.”

Although one inspiration for “Zero Positive” came from the death of a friend, Mr. Kondoleon points out that his fictional “seropositive” characters are no more dying “than anyone else you know.” Mr. Elliott, his new director, adds: “In fact, they’re not dying. They’ve just learned that they might have a possibility of dying. But we’re all going to die sooner or later. These people simply have a greater awareness of death, which makes for a greater awareness of life.” And despite the fact that the play tackles everything from the Iran-contra hearings to the Peloponnesian war, Mr. Elliott feels that “It’s not about the ‘grand themes.’ It’s about real people.”

Mr. Kondoleon himself shuns the oracular mantle. “”My play isn’t a lecture. And I’m not passing myself off as an expert on anything – except the world I’ve invented.”

New York Times, Sunday May 15, 1988